Jupiter’s moons: Names, number and exploration

When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission. Here’s how it works.

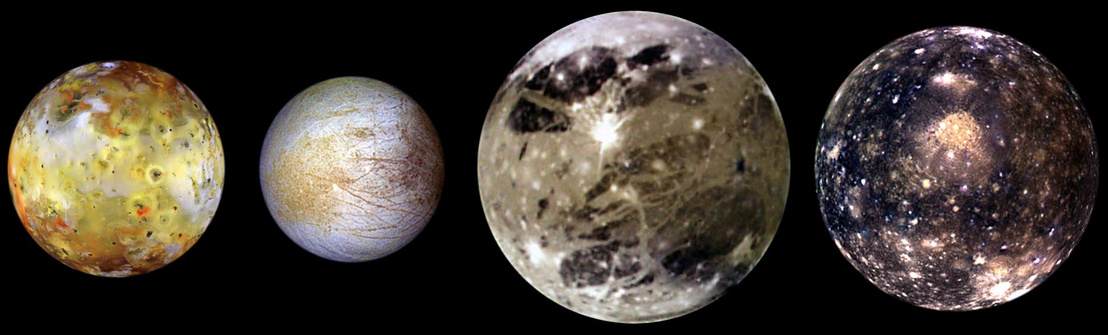

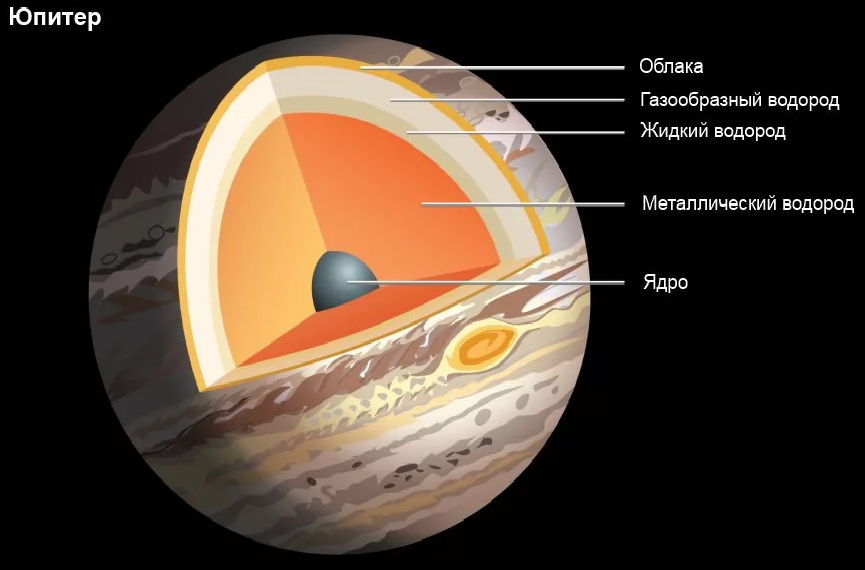

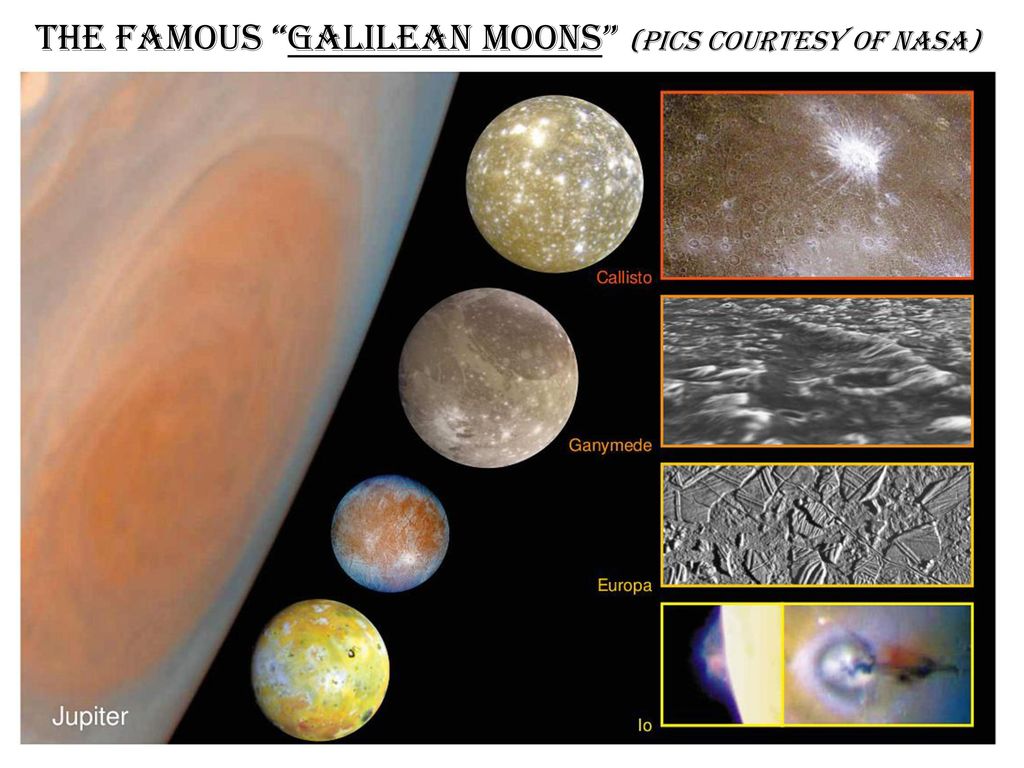

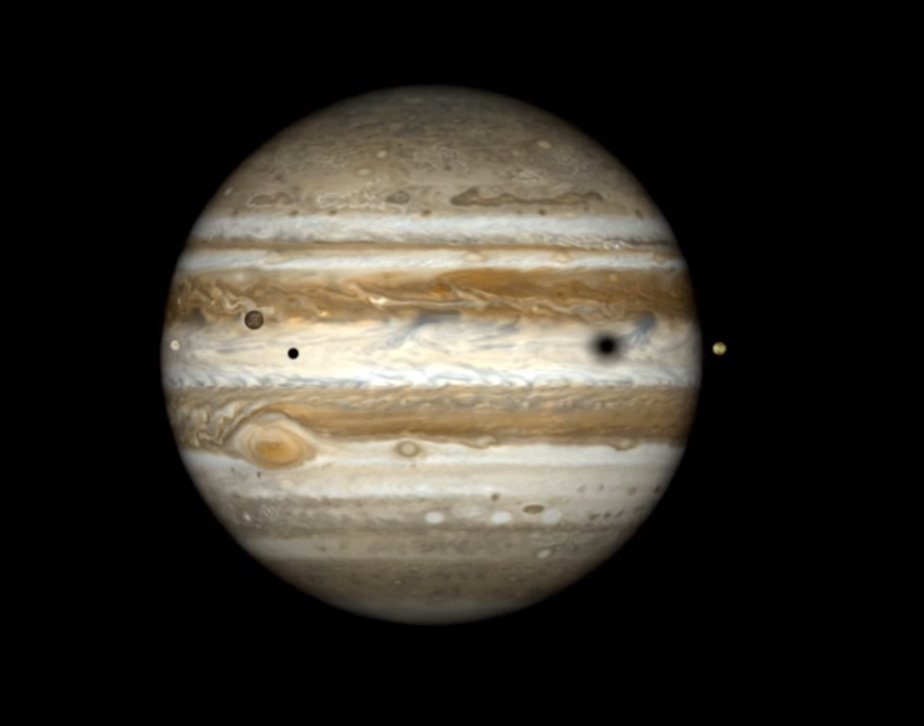

Jupiter’s four largest moons are known as the Galilean moons. This composite image shows from left to right, Ganymede, Callisto, Io and Europa.

(Image credit: NASA/JPL/DLR)

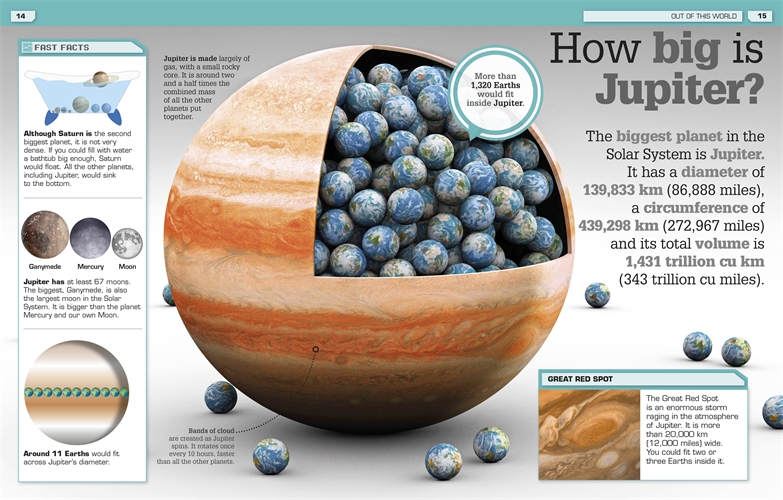

Jupiter has 80 moons in total, 57 are official and a further 23 are awaiting confirmation and naming by the International Astronomical Union.

Four of Jupiter‘s moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto — known as the Galilean moons — were the first celestial objects to be discovered orbiting an object other than the sun or Earth when Galileo Galilei first observed them in 1610.

Most of Jupiter’s moons are small, with about 60 of the satellites measuring less than 6.2 miles (10 kilometers) in diameter. Unusually, the outer moons orbit in the opposite direction to which Jupiter spins, suggesting they may have been captured by Jupiter’s gravitational field after the initial system was formed.

Related: The 10 weirdest moons in the solar system

Reference Writer

Daisy joined Space.com in February 2022, before that she worked as a staff writer for our sister publication All About Space magazine. Daisy has a Ph.D. in plant physiology and an MSci in environmental science.

Jupiter’s official moons: Names and discovery dates

Here is a list of all 57 official moons of Jupiter along with details on their discovery, according to NASA. There are still 23 moons awaiting confirmation by the International Astronomical Union.

Adrastea: Discovered in July 1979 by the Voyager science team.

Aitne: Discovered on 9 December 2001 by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna during observations at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Amalthea: Discovered on September 9, 1892, by American astronomer Edward Emerson Barnard.

Ananke: Discovered on September 28, 1951, by American astronomer Seth Barnes Nicholson from a photograph made using the 100-inch (2.

Aoede: Discovered on February 8, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Jan T. Kleyna, Yanga R. Fernandez, and Henry H. Hsieh during observations at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Arche: Discovered on October 31, 2002, by Scott S. Sheppard at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Autonoe: Discovered on December 10, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Callirrhoe: Discovered on October 19, 1999, by Jim V. Scotti, Timothy B. Spahr, Robert S. McMillan, Jeffrey A. Larsen, Joe Montani, Arianna E. Gleason, and Tom Gehrels from observations made with the 36-inch telescope on Kitt Peak. The discovery was made during a course of observations by the Spacewatch program of the University of Arizona.

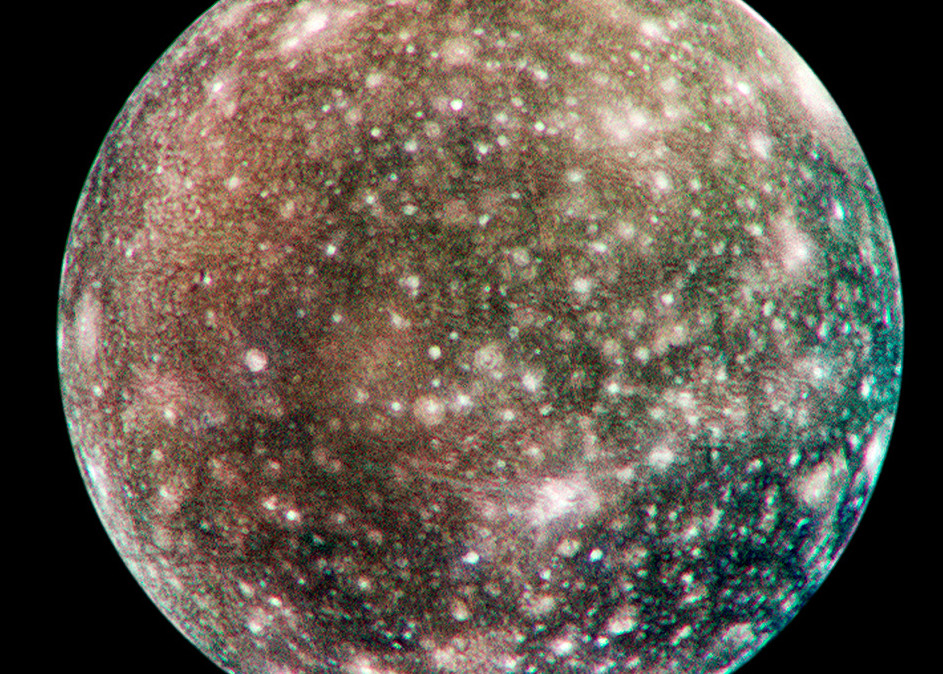

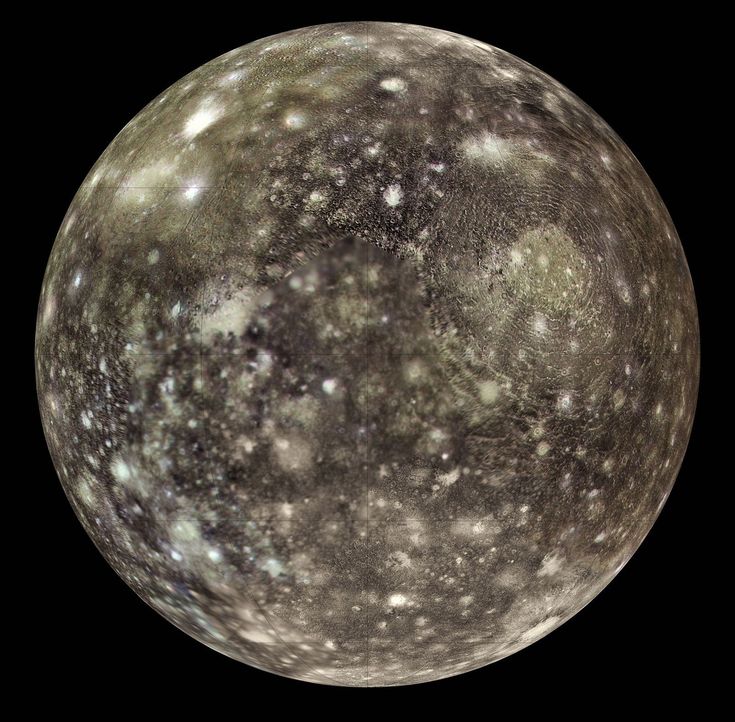

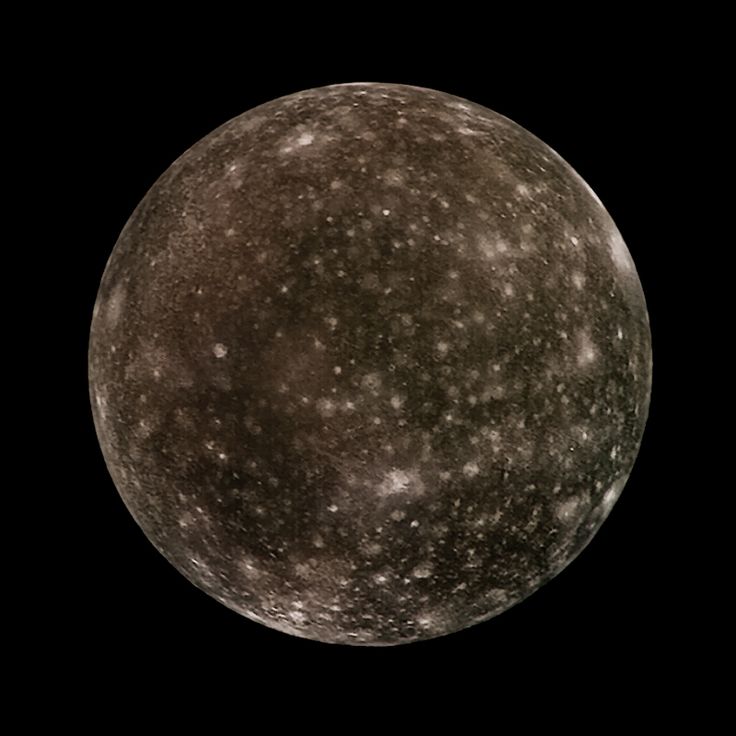

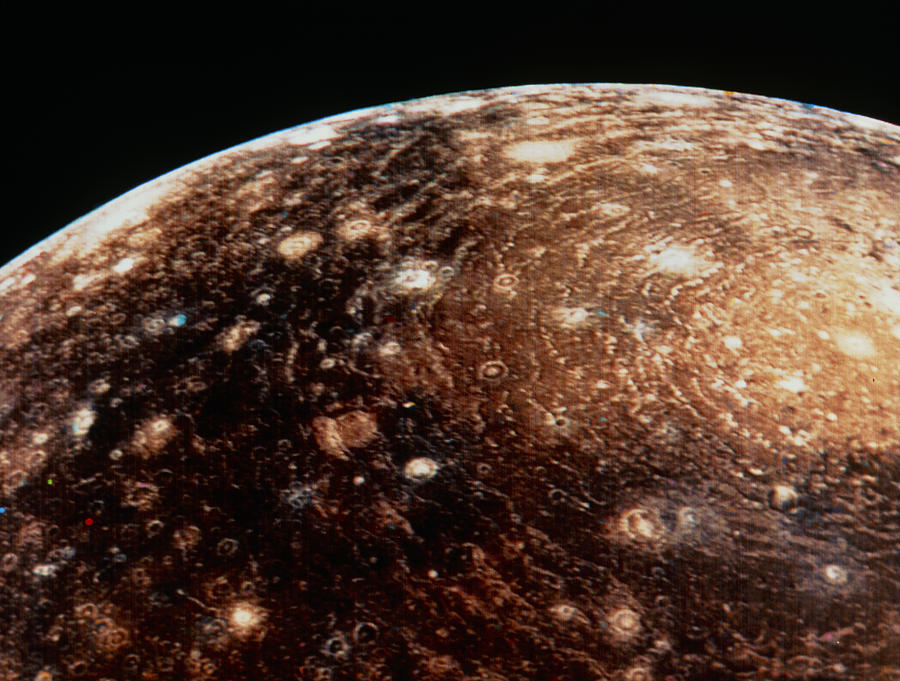

Callisto: Discovered on January 7, 1610, by Italian scientist Galileo Galilei.

Image of Callisto taken from NASA’s Galileo spacecraft. (Image credit: NASA/JPL/DLR)

Carme: Discovered on July 30, 1938, by Seth Barnes Nicholson during observations made with the 100-inch (2.5 m) Hooker telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory in California.

Carpo: Discovered on February 26, 2003, by a team of astronomers from the University of Hawaii’s Institute for Astronomy led by Scott S. Sheppard. The discovery was made using the 12-ft. (3.6-m) Canada-France-Hawaii telescope at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Chaldene: Discovered on November 23, 2000, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yange R. Fernandez, and Eugene Magnier at an observatory on Mauna Kea in Hawaii.

Cyllene: Discovered on February 9, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard and his team from the University of Hawaii at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Dia: Discovered on December 5, 2000, by Scott S.

Eirene: Discovered on February 6, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Elara: Discovered on January 5 1905, by American astronomer Charles Dillon Perrine while looking at photographs taken with the Crossley 36-inch (0.9 meter) reflector of the Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton at the University of California, San Jose.

Erinome: Discovered on November 23, 2000, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yanga R. Fernandez and Eugene Magnier at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Ersa: First spotted in 2017, the moon’s discovery by Scott S. Sheppard and his team was announced in July 2018.

Euanthe: Discovered on December 11, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Eukelade: Discovered on February 6, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Eupheme: Discovered on March 4, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii

Euporie: Discovered on December 11, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Europa: Discovered on January 8, 1610, by Italian scientist Galileo Galilei.

Eurydome: Discovered on December 9, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

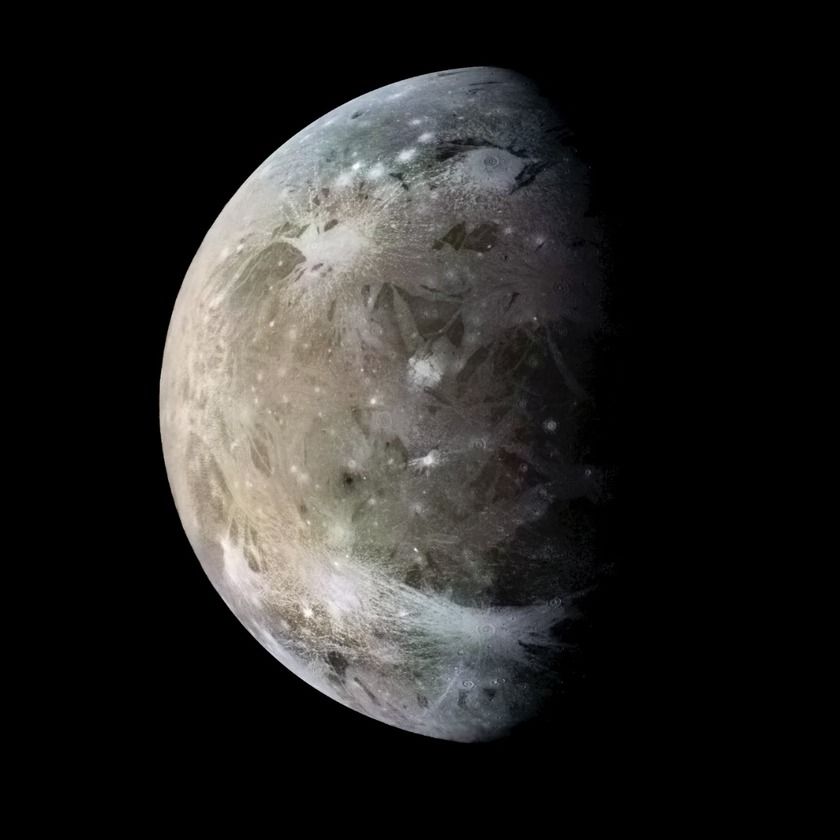

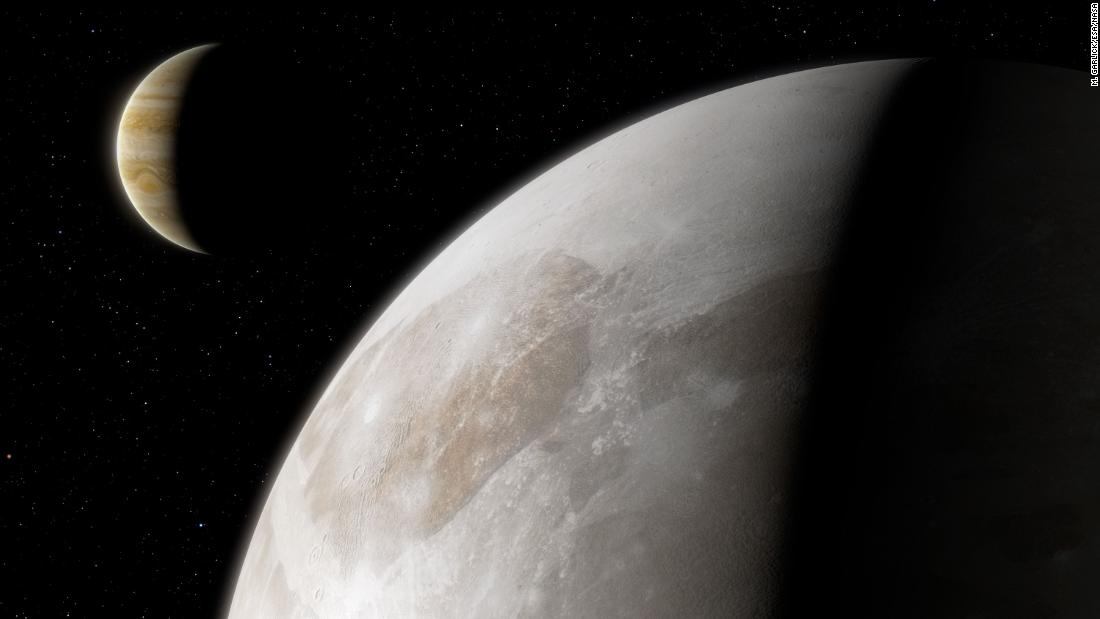

Ganymede: Discovered on January 7, 1610, by Italian scientist Galileo Galilei.

Harpalyke: Discovered on November 23, 2000, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yanga R. Fernandez, and Eugene Magnier at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Hegemone: Discovered on February 8, 2003, by Scott S.

Helike: Discovered on February 6, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Hermippe: Discovered on December 9, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Herse: Discovered on February 27, 2003, by Brett J. Gladman, John J. Kavelaars, Jean-Marc Petit, and Lynne Allen.

Himalia: Discovered on December 3, 1904, by American astronomer Charles Dillon Perrine while looking at photographs taken with the Crossley 36-inch (0.9 meter) reflector of the Lick Observatory on Mount Hamilton at the University of California, San Jose.

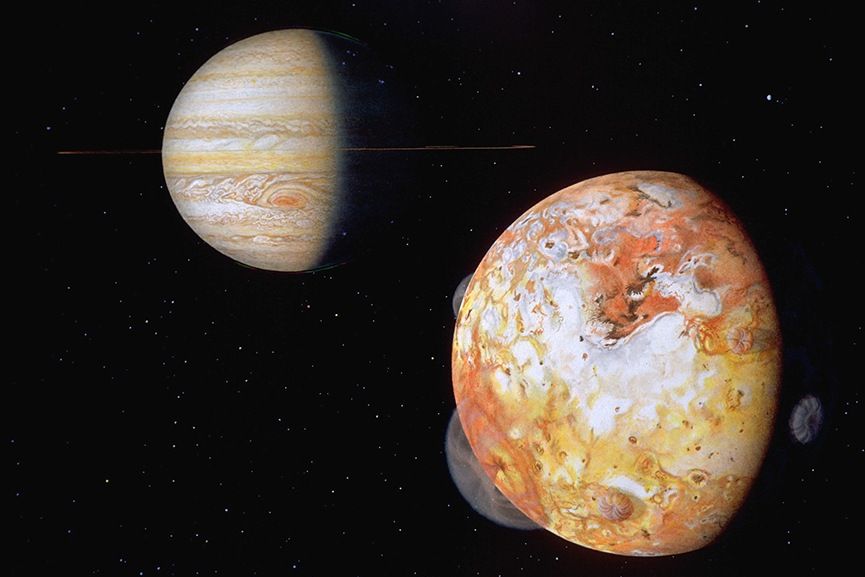

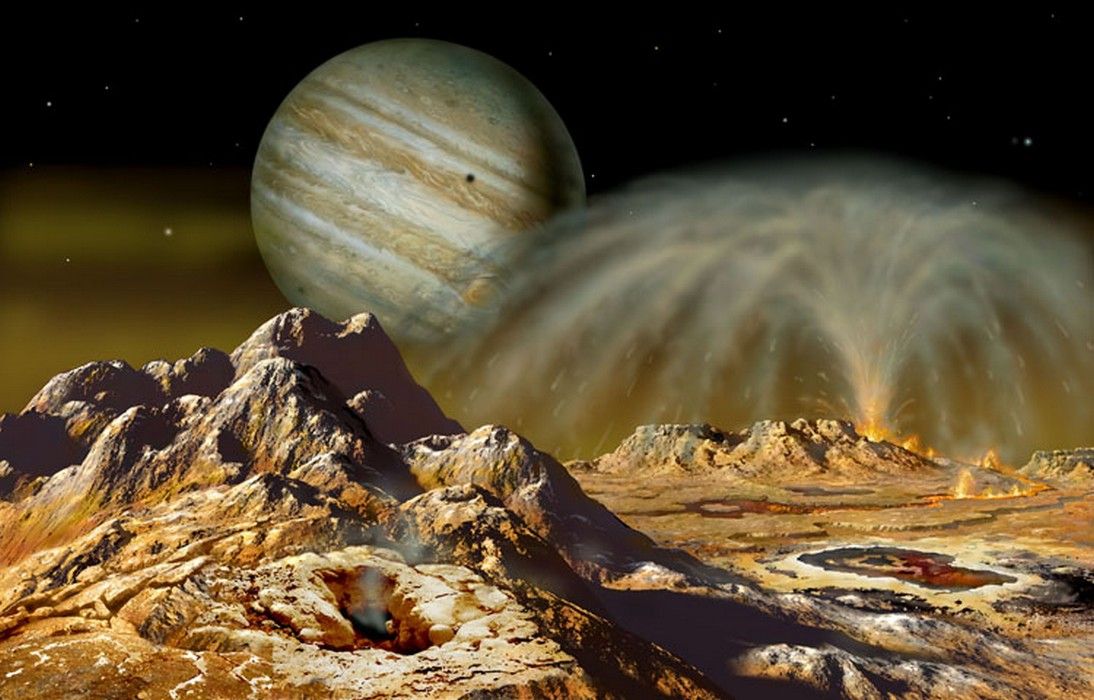

Io: Discovered on January 8, 1610, by Italian scientist Galileo Galilei.

Io imaged by NASA’s Galileo spacecraft. (Image credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona)

Iocaste: Discovered on November 23, 2000, by Scott S.

Isonoe: Discovered on November 23, 2000, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yanga R. Fernandez, and Eugene Magnier at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Kale: Discovered on December 9, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Kallichore: Discovered on February 6, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Kalyke: Discovered on November 23, 2000, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yanga R. Fernandez, and Eugene Magnier at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Kore: Discovered on February 8, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Leda: Discovered on September 14, 1974, by American astronomer Charles Thomas Kowal during observations of plates taken from Sept.

Lysithea: Discovered on July 6, 1938, by American astronomer Seth Barnes Nicholson with the 100-inch (2.5 m) Hooker telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory, California.

Megaclite: Discovered on November 25, 2000, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yanga R. Fernandez, and Eugene A. Magnier at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Metis: Discovered in March 1979 by the Voyager science team.

Related stories:

Mneme: Discovered on February 9, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard and Brett Joseph Gladman at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Orthosie: Discovered on December 11, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, Yanga R. Fernandez and David C. Jewitt at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Pandia: First spotted in 2017, the moon’s discovery by Scott S. Sheppard and his team was announced in July 2018.

Pasiphae: Discovered on January 27, 1908, by British astronomer Philibert Jacques Melotte with the Greenwich Observatory’s 30-inch Cassegrain telescope.

Pasithee: Discovered on December 11, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Philophrosyne: Discovered in April 2003 by Scott S. Sheppard at the Mauna Kea Observatory in Hawaii.

Praxidike: Discovered on November 23, 2000, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yanga R. Fernandez, and Eugene Magnier at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Sinope: Discovered on July 21, 1914, by American astronomer Seth Barnes Nicholson during observations of photographic plates taken with the Lick Observatory’s 36-inch (0.9 meter) telescope in California.

Sponde: Discovered on December 9, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Taygete: Discovered on November 25, 2000, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yanga R. Fernandez, and Eugene Magnier at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Thebe: Discovered in 1980 by the Voyager science team investigating images captured by Voyager 1.

Thelxinoe: Discovered on February 9, 2003, by Scott S. Sheppard and Brett J. Gladman at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Themisto: Discovered initially on September 30, 1975, by American astronomers Charles Thomas Kowal and Elizabeth Roemer. The little moon was then lost until 2000 when it was rediscovered by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt, Yanga Roland Fernandez and Eugene A. Magnier during their search for small irregular Jovian moons using the 27-foot (8.3m) Subaru telescope and the 11.8-foot (3.6m) Canada-French-Hawaii telescope at Mauna Kea Observatories, Hawaii.

Thyone: Discovered on December 11, 2001, by Scott S. Sheppard, David C. Jewitt and Jan T. Kleyna at the Mauna Kea Observatory, Hawaii.

Valetudo: First spotted in 2017, the moon’s discovery by Scott S.

Galilean moons: Jupiter’s biggest satellites

1. Ganymede

Diameter: 3,270 miles (5,260 kilometers)

Jupiter’s moon Ganymede is the biggest moon in the solar system, it is even larger than the planet Mercury. It is also the only moon that we know of to have its own magnetic field, which causes impressive polar light shows — auroras. Furthermore, the giant moon could harbor a subsurface saltwater ocean which has been theorized to hold more water than all the water on Earth’s surface, according to NASA Science.

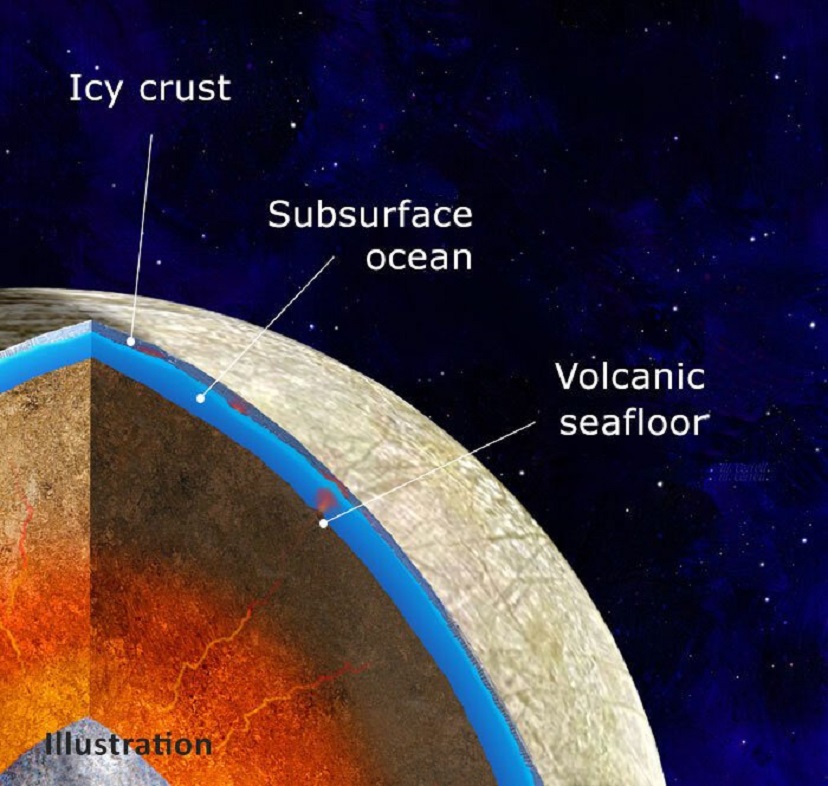

2. Europa

Diameter: 1,940 miles (3,100 km)

Europa is thought to have an iron core, rocky mantle and a surface of frozen water ice that sits atop a vast saltwater ocean. According to NASA , the icy moon Europa is thought to be the most promising place to find an environment that could support life forms beyond Earth. The theorized subsurface saltwater ocean could contain twice as much water as Earth’s oceans combined and have existed long enough for life to have possibly begun and even evolved.

3. Io

Diameter: 2,260 miles (3,640 km)

The most volcanically active place in the solar system, Io is a remarkable world locked in a “tug-of-war” between Jupiter’s gravity and pulls from neighboring Galilean moons Europa and Ganymede. The turbid environment continually renews itself , smoothing out craters with vast lakes of lava spewed from one of the hundreds of volcanoes that blanket the landscape.

4. Callisto

Diameter: 2,995 miles (4,820 km)

Jupiter’s second-largest moon Callisto is the third-largest moon in the solar system. The moon’s surface is thought to be about 4 billion years old , making it the oldest icy surface in the solar system. After being pummeled for4 billion years by impactors such as meteors, it comes as no surprise that Callisto also holds the record for the most heavily cratered body in the solar system.

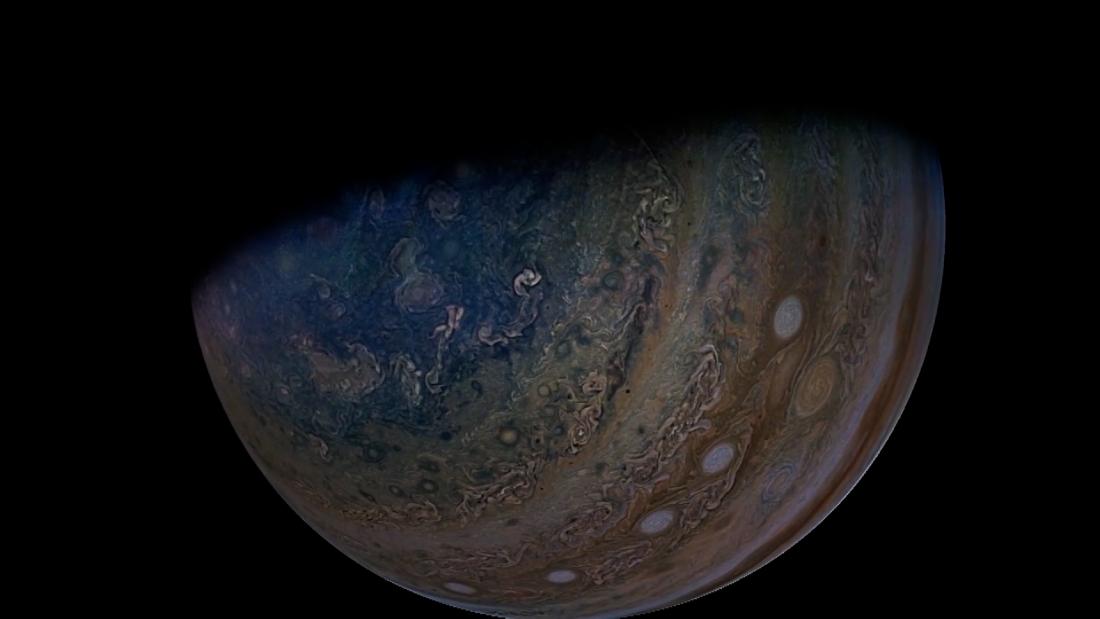

Exploration of Jupiter and its moons

NASA’s Galileo Orbiter was the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter.

The Jovian system is no stranger to guests. Since its first visitor in December 1973 when NASA’s Pioneer 10 spacecraft conducted a flyby of the gas giant, Jupiter has attracted numerous flybys and close encounters from trailblazing probes. Pioneer 11 made a close approach a year after Pioneer 10 in December 1974 and Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 flew past Jupiter in 1979.

But it wasn’t until NASA’s Galileo spacecraft approached the Jovian system in December 1995 that the gas giant finally had a guest stay for any significant length of time. Galileo was the first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter and made substantial discoveries about the gas giant and its moons. The spacecraft spent almost eight years in Jupiter’s neighborhood, revealing its many secrets, from a possible subsurface ocean on Jupiter’s icy moon Europa, to volcanoes on the moon Io. At the end of its stay in September 2003, Galileo intentionally crashed into the gas giant to prevent collisions and subsequent contamination with the Jovian moons.

The NASA-ESA Ulysses mission used Jupiter for a couple of gravity-assist maneuvers in 1992 and 2004 while en route to the sun and NASA’s Cassini-Huygens spacecraft also paid Jupiter a brief visit while journeying to Saturn. Cassini made its close approach to Jupiter in December 2000 and collected around 26,000 images of the gas giant in the process. Then NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft called in on Jupiter in February 2007 during its trip to Pluto and revealed impressive nighttime auroras and lightning near the planet’s poles.

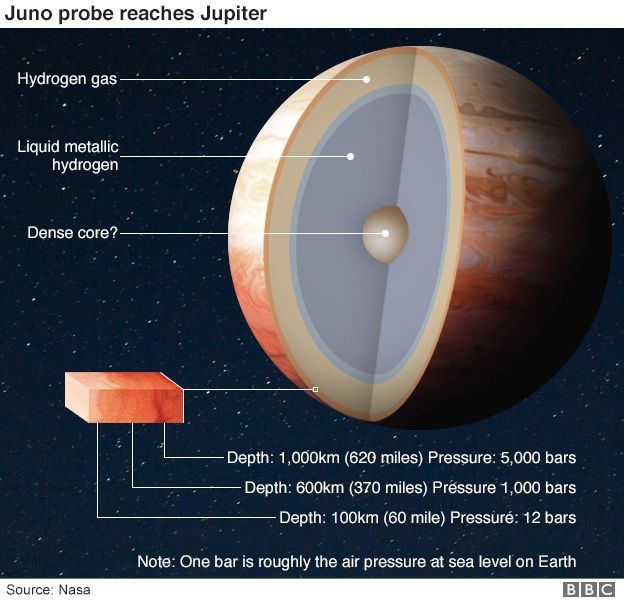

The Jovian system is currently being explored by NASA’s Juno mission which arrived in July 2016. Juno is only the second spacecraft to orbit Jupiter and is busy investigating its composition, atmosphere, gravity and magnetic field. Juno aims to learn more about the origin and evolution of Jupiter and the solar system.

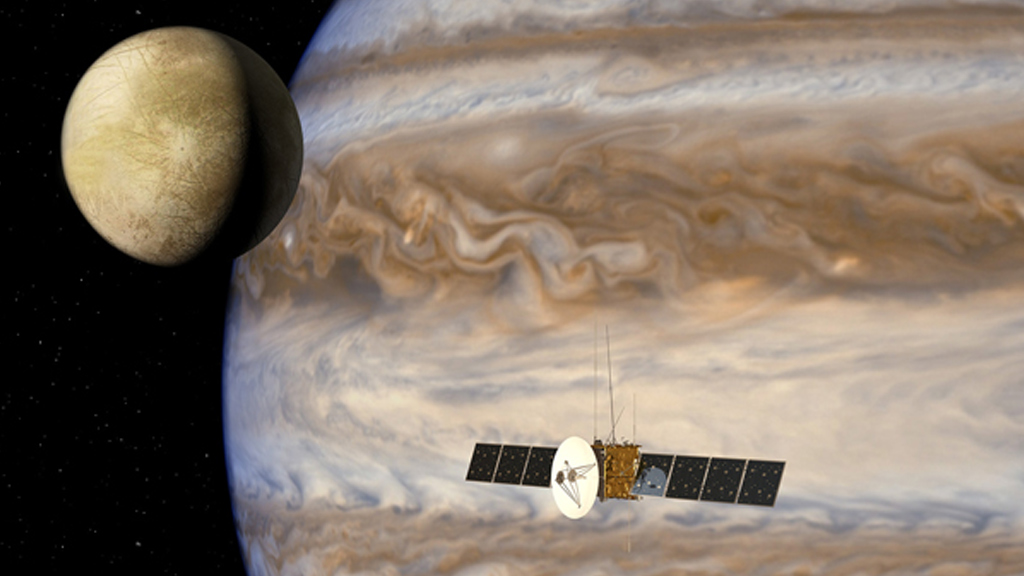

Next on the roster to visit the Jovian neighborhood is ESA’s Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer, JUICE, due to launch in April 2023. The mission will explore Jupiter and three of its Galilean moons: Ganymede, Callisto and Europa.

How to see Jupiter’s moons for yourself

With the right equipment, it is possible to spot Jupiter and its four Galilean moons. Our visible planets guide tells you where you can find the brightest planets that month and the best times to view them.

TOP TELESCOPE PICK:

(Image credit: Celestron)

Looking for a telescope to view the planets? We recommend the Celestron Astro Fi 102 as the top pick in our best beginner’s telescope guide.

Jupiter can reach magnitude -2.94 at this brightness you can spot the gas giant with the naked eye, a pair of binoculars or a small telescope. (On the magnitude scale used by astronomers, lower numbers signify brighter objects. For example, at its brightest, the planet Venus shines with a magnitude of about -4.

To find out where and when to look out for Jupiter’s moons, we recommend using skywatching apps like SkySafari or software like Starry Night. Our picks for the best stargazing apps may help you with your planning.

If you’re looking for a telescope or binoculars to observe Jupiter and its moons, our best telescopes for seeing planets guide can help. We also have guides on the best binoculars deals and the best telescope deals, which may come in useful when hunting for a bargain.

Additional resources

Learn more about ESA’s JUICE mission to Jupiter’s icy moons with this video from ESA . Read more about whether there could be life on Jupiter’s moons with this article by Jonathan O’Callaghan in the EU Research and Innovation magazine Horizon. Do you think you’ve discovered a new moon or something else exciting? The International Astronomical Union Report has a guide to the most common objects that you may have observed as well as information on how to officially report your findings .

Bibliography

ESA. Missions to Jupiter. ESA Science & Technology. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://sci.esa.int/web/juice/-/59909-missions-to-jupiter

NASA. Callisto. NASA. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/callisto/in-depth/

NASA. Europa Clipper. NASA. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/missions/europa-clipper

NASA. Io. NASA. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/io/in-depth

NASA. Jupiter moons. NASA. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/overview

NASA. Europa. NASA. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/europa/overview/

NASA. Ganymede. NASA. Retrieved October 21, 2022, from https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/jupiter-moons/ganymede/overview/

Williams, M. (June 10, 2015).

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: [email protected].

Daisy Dobrijevic joined Space.com in February 2022 having previously worked for our sister publication All About Space magazine as a staff writer. Before joining us, Daisy completed an editorial internship with the BBC Sky at Night Magazine and worked at the National Space Centre in Leicester, U.K., where she enjoyed communicating space science to the public. In 2021, Daisy completed a PhD in plant physiology and also holds a Master’s in Environmental Science, she is currently based in Nottingham, U.K.

Lunas de Júpiter – Información, descubrimiento, nombres, distancias

Te explicamos qué son las lunas de Júpiter, cómo fueron descubiertas y la lista con sus nombres.

Hay pocas lunas de mayor tamaño superiores a los 3100 kilómetros.

¿Qué son las lunas de Júpiter?

En astronomía, las lunas de Júpiter son el conjunto de satélites naturales que orbitan a este planeta gigante del Sistema solar exterior. Este planeta, como su nombre lo refleja (Júpiter es el nombre romano del dios griego Zeus, padre y regidor del Olimpo divino) es considerado a menudo el “rey” de los planetas dado su enorme tamaño, equivalente a 318 veces el de la Tierra.

Hasta el momento, se conoce la existencia de unas 79 lunas de Júpiter, lo cual lo convierte en el planeta de mayor séquito del Sistema solar. Estas lunas poseen características orbitales sumamente distintas, que van desde los recorridos orbitales circulares a los excéntricos e inclinados, en algunos casos girando en contra del sentido de rotación de Júpiter. En cuanto a su aspecto físico, las hay pocas de mayor tamaño, superiores a los 3100 kilómetros; mientras que el resto oscila entre los 5 y los 250 kilómetros.

Hasta el momento se piensa que las lunas de Júpiter se formaron del mismo cúmulo de gases y materia del que surgió el planeta, si bien las más pequeñas pueden ser el resultado de la destrucción de otros satélites previos de mayor tamaño, perdidos durante la historia temprana de Júpiter. Algunas incluso se asumen como producto directo del tránsito de los asteroides, seducidos por la enorme gravedad del planeta rey.

Ver además: Traslación de la Tierra

Descubrimiento de las lunas de Júpiter

El número total de satélites jupiterianos hoy en día asciende a 79.

Las cuatro lunas de mayor tamaño son llamadas los “satélites galileanos”, ya que fueron descubiertos en 1610 por el célebre Galileo Galilei, y fueron los primeros objetos astronómicos descubiertos orbitando alrededor de otro planeta, aunque existen registros de avistamientos informales atribuidos al astrónomo chino Gan De (c. 364 a. C.).

En 1892 se descubrió una luna adicional a las galileanas, y con la ayuda de mejores y más potentes telescopios, se siguieron añadiendo lunas a la lista en 1904, 1905, 1908, 1914, 1938, 1951 y 1974.

Nombre de las lunas de Júpiter

El listado de las numerosas lunas de Júpiter y sus respectivos nombres es el siguiente:

- Metis. De 43 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1979.

- Adrastea. De diámetro irregular (26x20x16), descubierta en 1979.

- Amaltea. De diámetro irregular (262x146x134), descubierta en 1892.

- Tebe. De diámetro irregular (110×90), descubierta en 1979.

- Io. De 3643 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1610.

- Europa. De 3122 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1610.

- Ganímedes. De 5262 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1610.

- Calisto. De 4821 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1610.

- Temisto. De 8 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1975.

- Leda. De 20 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1974.

- Himalia. De 170 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1904.

- Lisitea. De 36 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1938.

- Elara. De 86 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1905.

- Dia. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- Carpo. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- S/2003 J 12. De 1 kilómetro de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Euporia. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- S/2003 J 3. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- S/2003 J 18. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Ortosia. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- Euante. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- Harpálice. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- Praxídice. De 7 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- Tione. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- S/2003 J 16. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Yocasta. De 5 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- Mnemea. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Hermipé. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- Telxínoe. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Heliké. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Ananqué. De 28 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1951.

- S/2003 J 15. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Eurídome. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- Arce. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2002.

- Herse. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Pasítea. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- S/2003 J 10. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Caldona. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- Isonoé. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- Erínome. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- Calé. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- Aitné. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- Táigete. De 5 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- S/2003 J 9. De 1 kilómetro de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Carmé. De 46 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1938.

- Espondé. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- Megaclite. De 5 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- S/2003 J 5. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- S/2003 J 19. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- S/2003 J 23. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Cálice. De 5 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2000.

- Pasifae. De 60 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1908.

- Eukélade. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- S/2003 J 4. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Sinope. De 38 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1914.

- Hegémone. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Cilene. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Aedea. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Kore. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Kallichore. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- Autónoe. De 4 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2001.

- Calírroe. De 9 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 1999.

- S/2003 J 2. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2003.

- S/2010 J 1. De 1 kilómetro de diámetro, descubierta en 2010.

- S/2010 J 2. De 1 kilómetro de diámetro, descubierta en 2010.

- S/2011 J 1. De 1 kilómetro de diámetro, descubierta en 2011.

- S/2011 J 2. De 1 kilómetro de diámetro, descubierta en 2011.

- S/2016 J 1. De 3 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2016.

- S/ 2017 J 1. De 2 kilómetros de diámetro, descubierta en 2017.

¿A qué distancia se encuentran las lunas de Júpiter?

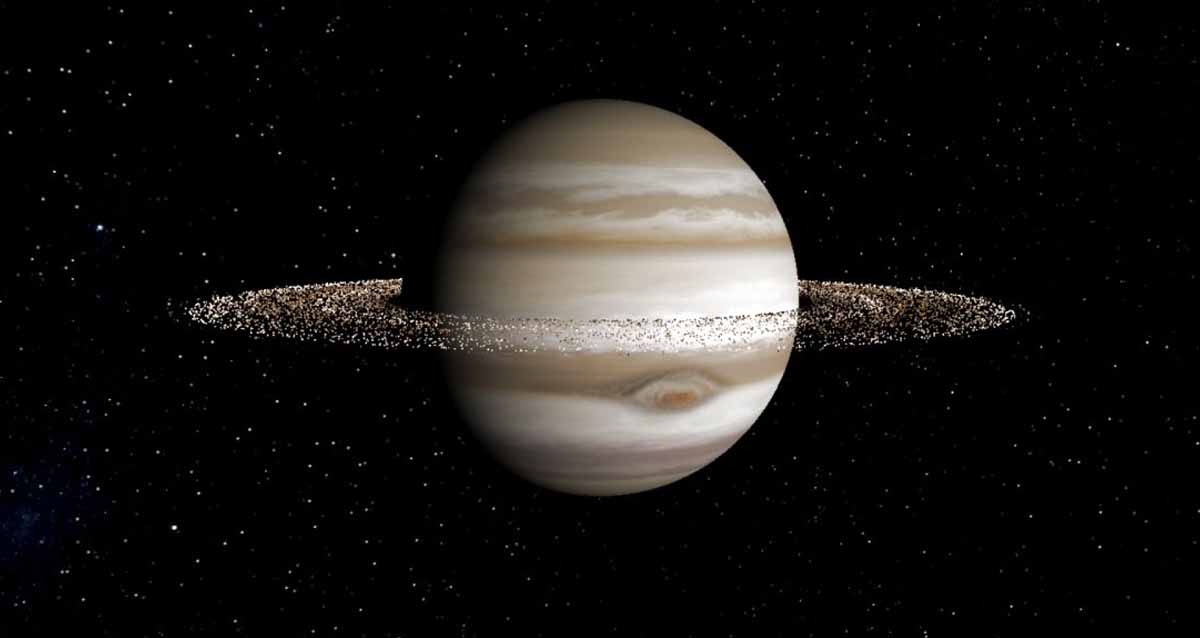

Los anillos de Júpiter orbitan el planeta a 122.800 km del centro.

Las numerosas lunas de Júpiter orbitan alrededor suyo en distintos niveles. Algunas de las diminutas forman, junto al polvo y gas, los anillos de Júpiter, que orbitan el planeta a 122.800 km del centro, con un espesor de una decena de kilómetros. Mucho más cerca del planeta, los satélites galileanos se encuentran como una primera frontera satelital, seguida de un grupo progrado que orbita en un espacio medio. Todo ello, claro está, a unos 594 millones de kilómetros de nuestro planeta.

Lunas de Júpiter que poseen agua

Desde hace mucho se estudia a las más grandes lunas de Júpiter como posibles hospedadoras de la humanidad, lo cual pasa por confirmar la existencia de agua (generalmente congelada).

Referencias

- “Satélites de Júpiter” en Wikipedia.

- “Lunas de Júpiter” en Astronoo.

- “¿Cuántas lunas tiene Júpiter? Todo lo que deberías saber” en Misistemasolar.com.

- “Jupiter Moons” en NASA.

- “Jupiter Moons: Crash Course Astronomy #17” (video) en Crash Course.

- “Descubren 12 nuevas lunas de Júpiter, incluyendo una ‘bola extraña’ que puede colisionar frontalmente con las demás” en BBC Mundo.

¿Cómo citar?

“Lunas de Júpiter”. Autor: Equipo editorial, Etecé.

Disponible en: https://concepto.de/lunas-de-jupiter/.

Última edición: 5 de agosto de 2021.

Consultado:

22 de abril de 2023

Sobre el autor

Compartir

Somehow we went to the Jupiter, Moon and Venus bar or one of the most spectacular astronomical events of 2023 – Sciencepop on DTF

should not be missed.

13,813

views

The outgoing winter, frankly speaking, was stingy with sunny days and clear starry nights. There were probably fewer of them than there are planets in the solar system. But the worst thing about this is not even a vitamin D deficiency, but the impossibility of astronomical observations. However, yesterday, as if by order, winter came to its senses, cheered up with a pleasant frost and gave a great opportunity to enjoy one of the most impressive celestial phenomena of 2023 – the conjunction of the king of the planets Jupiter, dazzling Venus and our constant companion of the Moon in the form of a thin sickle.

By the way, I recommend everyone who is not indifferent to the starry sky not to put away their binoculars, telescopes, cameras with phones, and, above all, their own eyes. They will come in handy for you very soon. With each February evening, Venus and Jupiter tend to get closer to each other, and literally on March 2, another rare and spectacular phenomenon will occur – their close visual convergence. The main thing is to be lucky again with the weather. The distance between them will be only half a degree! That is, approximately like the disk of the full moon.

The two brightest planets of our system will come together in a passionate dance, marking the beginning of spring. True, then Jupiter will leave without calling back.

Here they are from left to right: Jupiter, Moon, Venus

Let’s look at this phenomenon a little wider

And now we will remove all unnecessary

Take a picture, like it’s beautiful

Lower and lower over the resting city

The moon is tired and decided to sit on the roof of high-rise building

Fucking wires

Some signature

We are slowly approaching the landing

Venus has almost gone behind the houses and the atmosphere has dimmed its radiance

The powers of the Moon are also everything, but Jupiter is still holding on.

Thank you for your attention, clear sky to all!

ARE WE CHILDREN OF THE MOON AND JUPITER?

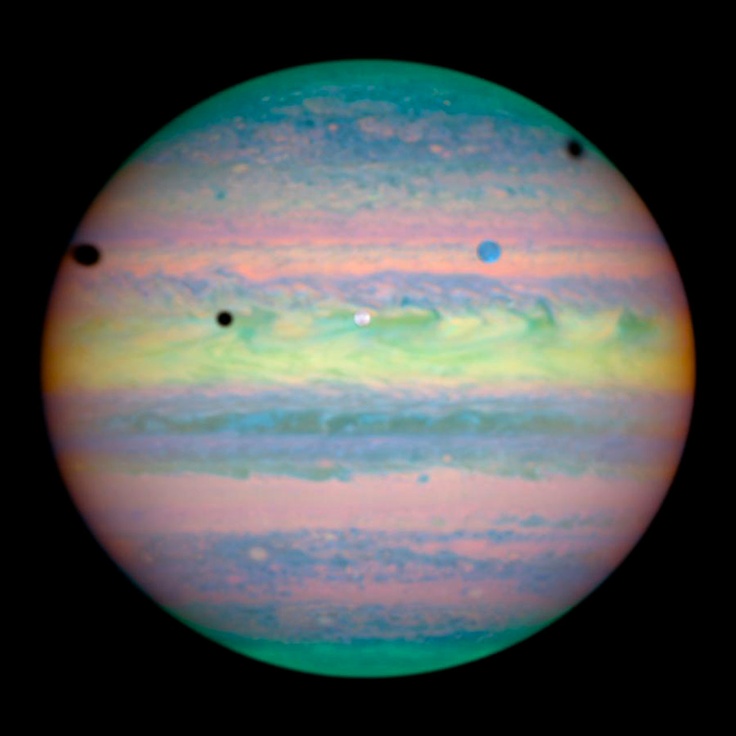

On the surface of Jupiter, the gas giant, there are no traces of meteorite impacts. But his satellites are dotted with such traces. The picture shows a straight chain of craters on the surface of Ganymede, similar to the trace of a burst from a huge space machine gun.

View full size

‹

›

The planets of the solar system have a total of more than seven dozen natural satellites (apparently, not all satellites of distant planets have been discovered yet, so it is too early to insist on the exact number). But only the Earth is so lucky with the Moon that from time to time we can observe total solar eclipses. The fact is that, although the diameter of the Moon is 400 times smaller than the diameter of the Sun, it is 400 times closer to us than the central luminary, so that their apparent size is the same, and the Moon has a chance to periodically obscure the Sun from the inhabitants of the Earth with its disk.

Since tidal friction gradually slows down the Moon (it spends the energy of its movement on moving water in the oceans and lifting sections of the earth’s crust), the satellite slowly moves away from the Earth. Therefore, total solar eclipses could be observed on our planet only in the last 150 million years, and about the same amount they will be visible in the future. It is now believed that the Moon was formed from molten magma torn from the body of the Earth in a collision with some large celestial body more than four billion years ago, and at first was much closer to the planet that gave birth to it.

The American astronomer Guillermo Gonzalez believes that such a coincidence of the apparent sizes of day and night luminaries is not a pure coincidence, and that it is precisely because of such a coincidence that there is intelligent life on Earth. Here are his arguments.

First, it is no coincidence that the distance of the Earth from the Sun. If the planet were a little closer to it – it would be too hot for life to arise here (as, for example, on Venus), and a little further – the Earth would be a kingdom of ice, also unsuitable for life.

Secondly, a large satellite located close to the Earth stabilizes its rotation, reduces the possibility of “wobbles” around the axis, which would lead to wild and unpredictable climate changes (this, apparently, happened on Mars, which has two, but very small satellite). Such jumps in conditions would also prevent the emergence of life.

Thirdly, the tides caused by the Moon create a humid zone on the shores of the earth’s oceans, which is either flooded or dried up. It was here that life could come to land. And in the water, she could not become intelligent, because she lives too well there – constant temperature, food floats around and almost climbs into her mouth, there are no problems with finding water; it is not necessary to build dwellings; easy to move; it is impossible to use fire, which means that the emergence of industry is impossible … All this does not require the development of the mind and does not contribute to it.

So humanity ultimately owes its existence to the moon, Gonzalez said.

According to the American geologist Peter Ward, not only the Moon, but also Jupiter must be thanked for our existence. The Earth, in comparison with other planets, bears relatively few large craters from collisions with comets and asteroids. Ward suggests that the orbit of our planet is so well located that the huge Jupiter, with its powerful gravitational field, “sweeps” almost all large fragments of space debris out of the Earth’s path. If not for the gas giant, frequent bombardment from space would make it difficult for non-microscopic life forms to emerge. And here we are very lucky. In recent years, it has been found that some stars have supermassive planets like Jupiter, but their orbits are either unstable or too close to the central star, and the emergence of life in such solar systems is unlikely.