Spain | History, Map, Flag, Population, Currency, Climate, & Facts

flag of Spain

Audio File:

National anthem of Spain

See all media

- Head Of Government:

- Prime Minister: Pedro Sánchez

- Capital:

- Madrid

- Population:

- (2023 est.) 47,900,000

- Currency Exchange Rate:

- 1 USD equals 0.905 euro

- Head Of State:

- King: Felipe VI

See all facts & stats →

Recent News

Apr. 25, 2023, 10:43 AM ET (AP)

Spain pleads for EU crisis funds as drought hits farmers

Spain’s Agriculture Minister Luis Planas has requested emergency funds from the European Union to support farmers and ranchers amid extreme drought conditions in the country’s agricultural heartlands

Apr. 19, 2023, 8:59 PM ET (AP)

Spain’s Sánchez warns drought now a major national concern

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has warned lawmakers that the acute drought afflicting the southern European country will remain one of its leading long-term problems

Apr. 18, 2023, 3:25 PM ET (AP)

Rivalry between Barcelona and Madrid takes turn for worse

The days of a healthy rivalry between Barcelona and Real Madrid are over

Apr. 18, 2023, 10:20 AM ET (AP)

Spain’s Barcelona faces drought ’emergency’ in September

Authorities in Spain’s parched northeast have warned that Barcelona and a surrounding area that’s home to some 6 million people could face even tighter restrictions of water use in the coming months

Apr. 18, 2023, 9:22 AM ET (AP)

Spain frees up ‘bad bank’ houses to ease housing crisis

Spain’s leftist coalition government has approved a plan to make available some 50,000 houses for rent at affordable prices as part of measures aimed at curbing soaring rents and house prices

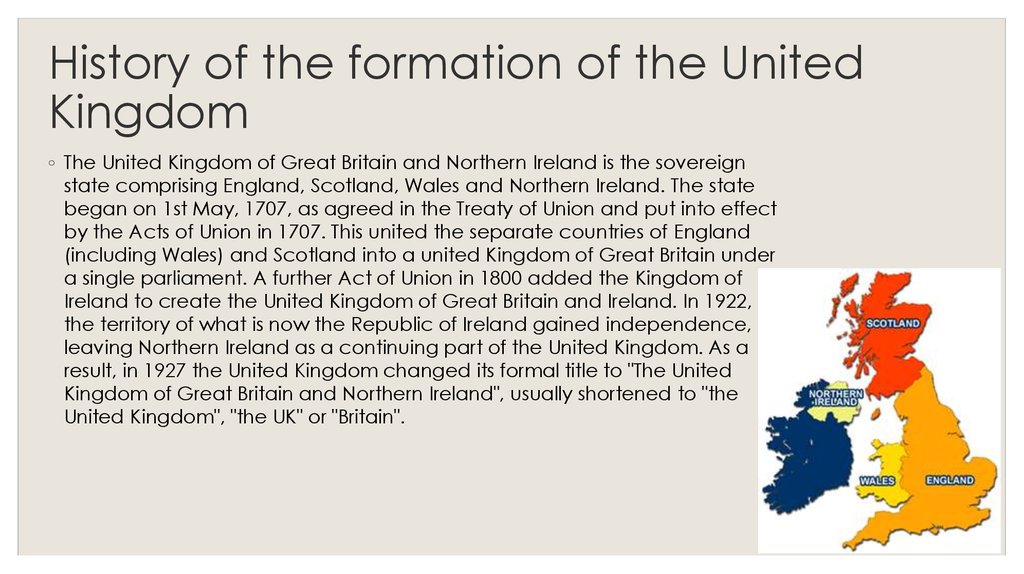

Spain, country located in extreme southwestern Europe.

Spain is a storied country of stone castles, snowcapped mountains, vast monuments, and sophisticated cities, all of which have made it a favoured travel destination. The country is geographically and culturally diverse. Its heartland is the Meseta, a broad central plateau half a mile above sea level. Much of the region is traditionally given over to cattle ranching and grain production; it was in this rural setting that Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote tilted at the tall windmills that still dot the landscape in several places. In the country’s northeast are the broad valley of the Ebro River, the mountainous region of Catalonia, and the hilly coastal plain of Valencia. To the northwest is the Cantabrian Mountains, a rugged range in which heavily forested, rain-swept valleys are interspersed with tall peaks. To the south is the citrus-orchard-rich and irrigated lands of the valley of the Guadalquivir River, celebrated in the renowned lyrics of Spanish poets Federico García Lorca and Antonio Machado; over this valley rises the snowcapped Sierra Nevada.

Spain’s countryside is quaint, speckled with castles, aqueducts, and ancient ruins, but its cities are resoundingly modern. The Andalusian capital of Sevilla (Seville) is famed for its musical culture and traditional folkways; the Catalonian capital of Barcelona for its secular architecture and maritime industry; and the national capital of Madrid for its winding streets, its museums and bookstores, and its around-the-clock lifestyle. Madrid is Spain’s largest city and is also its financial and cultural centre, as it has been for hundreds of years.

The many and varied cultures that have gone into the making of Spain—those of the Castilians, Catalonians, Lusitanians, Galicians, Basques, Romans, Arabs, Jews, and Roma (Gypsies), among other peoples—are renowned for their varied cuisines, customs, and prolific contributions to the world’s artistic heritage.

Britannica Quiz

Countries of the World

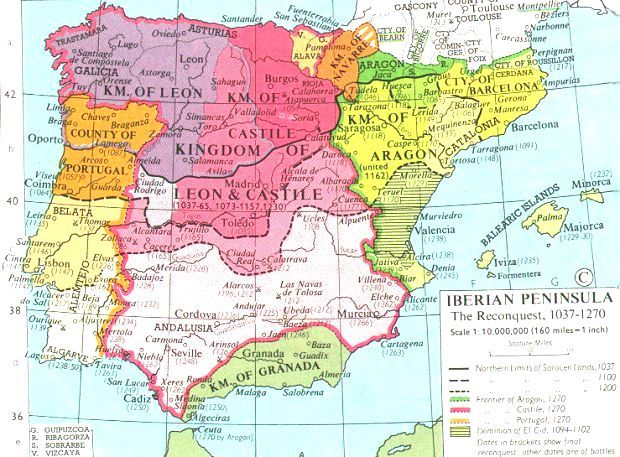

In 1492, the year the last of the Moorish rulers were expelled from Spain, ships under the command of Christopher Columbus reached America.

Land

Spain is bordered to the west by Portugal; to the northeast it borders France, from which it is separated by the tiny principality of Andorra and by the great wall of the Pyrenees Mountains.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

Subscribe Now

Relief

Spain accounts for five-sixths of the Iberian Peninsula, the roughly quadrilateral southwestern tip of Europe that separates the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean.

Spain has some of the oldest as well as some of the youngest rocks of Europe. The entire western half of Iberia, with the exception of the extreme south, is composed of ancient (Hercynian) rocks; geologists refer to this Hercynian block as the Meseta Central. It constitutes a relatively stable platform around which younger sediments accumulated, especially on the Mediterranean side. In due course these sediments were pushed by major earth movements into mountain ranges. The term meseta is also used by geographers and local toponymy to designate the dominating relief unit of central Iberia. As a result, the Meseta Central defined by relief is subdivided by geology into a crystalline west (granites and gneisses) and a sedimentary east (mainly clays and limestones). The northern Meseta Central, which has an average elevation of 2,300 feet (700 metres), corresponds to the tablelands, or plateau, of Castile and León, although it is in fact a basin surrounded by mountains and drained by the Douro (Duero) River.

Part of Alpine Europe, the Pyrenees form a massive mountain range that stretches from the Mediterranean Sea to the Bay of Biscay, a distance of some 270 miles (430 km). The range comprises a series of parallel zones: the central axis, a line of intermediate depressions, and the pre-Pyrenees. The highest peaks, formed from a core of ancient crystalline rocks, are found in the central Pyrenees—notably Aneto Peak at 11,168 feet (3,404 metres)—but those of the west, including Anie Peak at 8,213 feet (2,503 metres), are not much lower. The mountains fall steeply on the northern side but descend in terraces to the Ebro River trough in the south. The outer zones of the Pyrenees are composed of sedimentary rocks. Relief on the nearly horizontal sedimentary strata of the Ebro depression is mostly plain or plateau, except at the eastern end where the Ebro River penetrates the mountains to reach the Mediterranean Sea.

A series of sierras trending northwest-southeast forms the Iberian Cordillera, which separates the Ebro depression from the Meseta and reaches its highest elevation with Moncayo Peak at 7,588 feet (2,313 metres).

Drainage

Although some maintain that “aridity rivals civil war as the chief curse of [historic] Spain,” the Iberian Peninsula has a dense network of streams, three of which rank among Europe’s longest: the Tagus at 626 miles (1,007 km), the Ebro at 565 miles (909 km), and the Douro at 556 miles (895 km).

Soils

There are five major soil types in Spain. Two are widely distributed but of limited extent: alluvial soils, found in the major valleys and coastal plains, and poorly developed, or truncated, mountain soils. Brown forest soils are restricted to humid Galicia and Cantabria. Acidic southern brown earths (leading to restricted crop choice) are prevalent on the crystalline rocks of the western Meseta, and gray, brown, or chestnut soils have developed on the calcareous and alkaline strata of the eastern Meseta and of eastern Spain in general.

Soil erosion resulting from the vegetation degradation suffered by Spain for at least the past 3,000 years has created extensive badlands, reduced soil cover, downstream alluviation, and, more recently, silting of dams and irrigation works. Particularly affected are the high areas of the central plateau and southern and eastern parts of Spain. Although the origins of some of the spectacular badlands of southeastern Spain, such as Guadix, may lie in climatic conditions from earlier in Quaternary time (beginning 2.6 million years ago), one of the major problems of modern Spain is the threat of desertification—i.e., the impoverishment of arid, semiarid, and even some humid ecosystems caused by the joint impact of human activities and drought.

Spain | History, Map, Flag, Population, Currency, Climate, & Facts

flag of Spain

Audio File:

National anthem of Spain

See all media

- Head Of Government:

- Prime Minister: Pedro Sánchez

- Capital:

- Madrid

- Population:

- (2023 est.) 47,900,000

- Currency Exchange Rate:

- 1 USD equals 0.905 euro

- Head Of State:

- King: Felipe VI

See all facts & stats →

Recent News

Apr.

Spain pleads for EU crisis funds as drought hits farmers

Spain’s Agriculture Minister Luis Planas has requested emergency funds from the European Union to support farmers and ranchers amid extreme drought conditions in the country’s agricultural heartlands

Apr. 19, 2023, 8:59 PM ET (AP)

Spain’s Sánchez warns drought now a major national concern

Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez has warned lawmakers that the acute drought afflicting the southern European country will remain one of its leading long-term problems

Apr. 18, 2023, 3:25 PM ET (AP)

Rivalry between Barcelona and Madrid takes turn for worse

The days of a healthy rivalry between Barcelona and Real Madrid are over

Apr. 18, 2023, 10:20 AM ET (AP)

Spain’s Barcelona faces drought ’emergency’ in September

Authorities in Spain’s parched northeast have warned that Barcelona and a surrounding area that’s home to some 6 million people could face even tighter restrictions of water use in the coming months

Apr.

Spain frees up ‘bad bank’ houses to ease housing crisis

Spain’s leftist coalition government has approved a plan to make available some 50,000 houses for rent at affordable prices as part of measures aimed at curbing soaring rents and house prices

Spain, country located in extreme southwestern Europe. It occupies about 85 percent of the Iberian Peninsula, which it shares with its smaller neighbour Portugal.

Spain is a storied country of stone castles, snowcapped mountains, vast monuments, and sophisticated cities, all of which have made it a favoured travel destination. The country is geographically and culturally diverse. Its heartland is the Meseta, a broad central plateau half a mile above sea level. Much of the region is traditionally given over to cattle ranching and grain production; it was in this rural setting that Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote tilted at the tall windmills that still dot the landscape in several places.

Spain’s countryside is quaint, speckled with castles, aqueducts, and ancient ruins, but its cities are resoundingly modern.

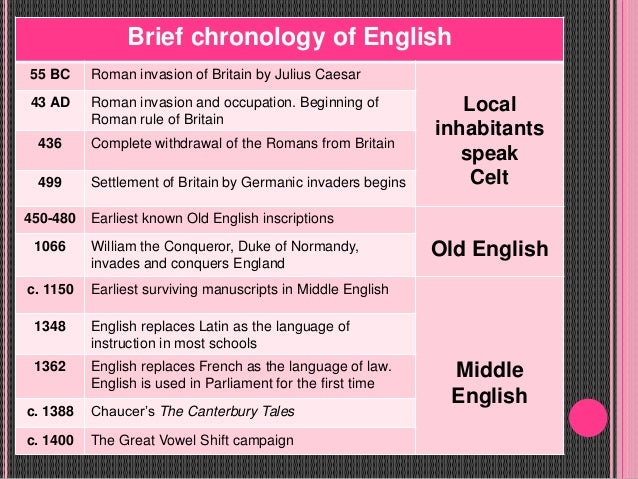

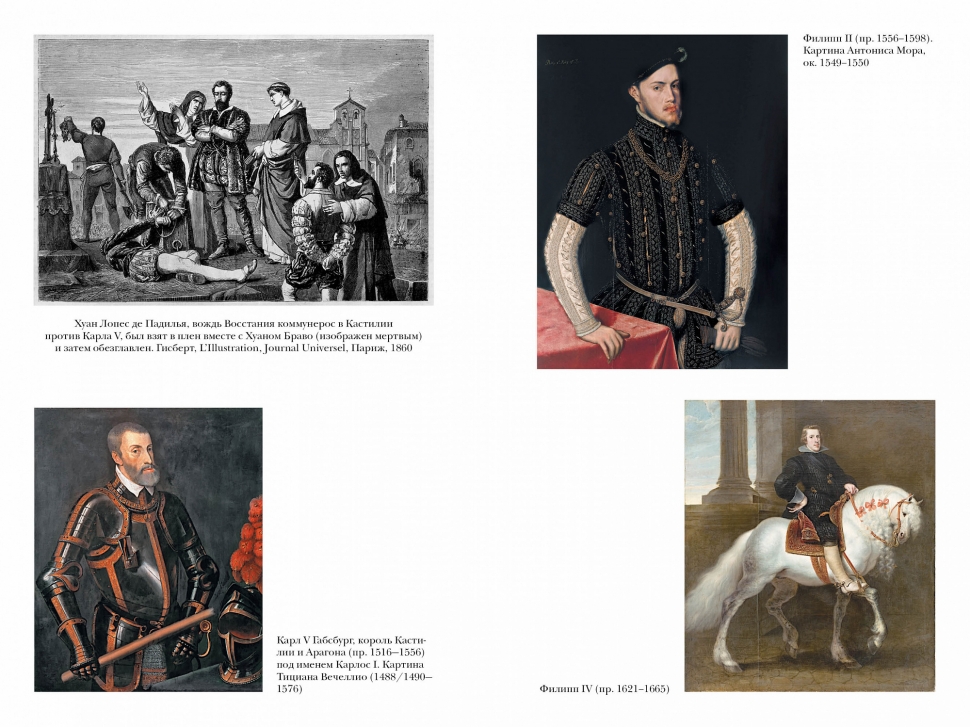

The many and varied cultures that have gone into the making of Spain—those of the Castilians, Catalonians, Lusitanians, Galicians, Basques, Romans, Arabs, Jews, and Roma (Gypsies), among other peoples—are renowned for their varied cuisines, customs, and prolific contributions to the world’s artistic heritage. The country’s Roman conquerors left their language, roads, and monuments, while many of the Roman Empire’s greatest rulers were Spanish, among them Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius. The Moors, who ruled over portions of Spain for nearly 800 years, left a legacy of fine architecture, lyric poetry, and science; the Roma contributed the haunting music called the cante jondo (a form of flamenco), which, wrote García Lorca, “comes from remote races and crosses the graveyard of the years and the fronds of parched winds.

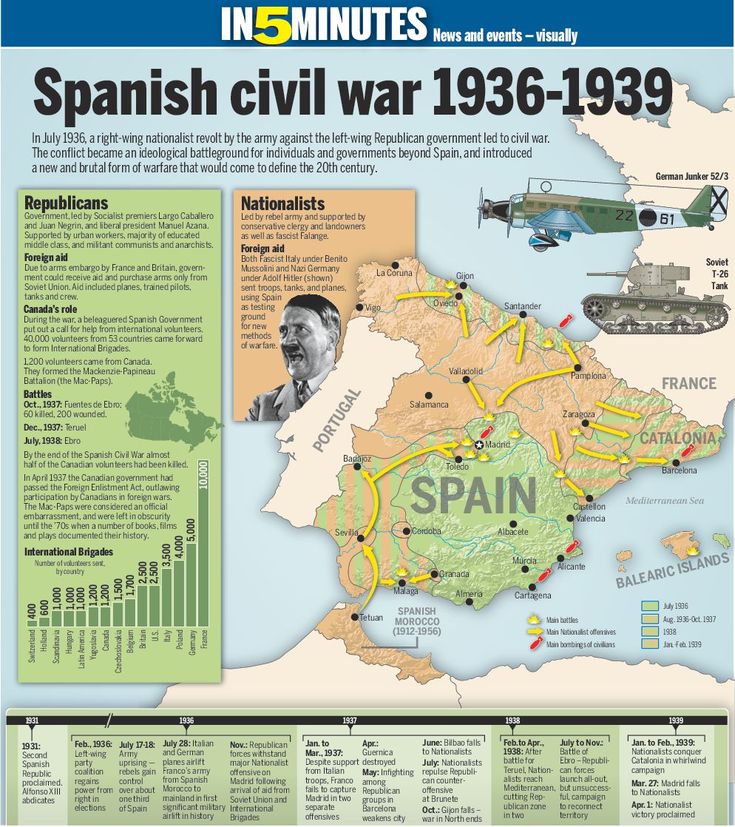

Britannica Quiz

A Visit to Europe

In 1492, the year the last of the Moorish rulers were expelled from Spain, ships under the command of Christopher Columbus reached America. For 300 years afterward, Spanish explorers and conquerors traveled the world, claiming huge territories for the Spanish crown, a succession of Castilian, Aragonese, Habsburg, and Bourbon rulers. For generations Spain was arguably the richest country in the world, and certainly the most far-flung. With the steady erosion of its continental and overseas empire throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, however, Spain was all but forgotten in world affairs, save for the three years that the ideologically charged Spanish Civil War (1936–39) put the country at the centre of the world’s stage, only to become ever more insular and withdrawn during the four decades of rule by dictator Francisco Franco.

Land

Spain is bordered to the west by Portugal; to the northeast it borders France, from which it is separated by the tiny principality of Andorra and by the great wall of the Pyrenees Mountains. Spain’s only other land border is in the far south with Gibraltar, an enclave that belonged to Spain until 1713, when it was ceded to Great Britain in the Treaty of Utrecht at the end of the War of the Spanish Succession. Elsewhere the country is bounded by water: by the Mediterranean Sea to the east and southeast, by the Atlantic Ocean to the northwest and southwest, and by the Bay of Biscay (an inlet of the Atlantic Ocean) to the north. The Canary (Canarias) Islands, in the Atlantic Ocean off the northwestern African mainland, and the Balearic (Baleares) Islands, in the Mediterranean, also are parts of Spain, as are Ceuta and Melilla, two small enclaves in North Africa (northern Morocco) that Spain has ruled for centuries.

Get a Britannica Premium subscription and gain access to exclusive content.

Subscribe Now

Relief

Spain accounts for five-sixths of the Iberian Peninsula, the roughly quadrilateral southwestern tip of Europe that separates the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean. Most of Spain comprises a large plateau (the Meseta Central) divided by a mountain range, the Central Sierra (Sistema Central), which trends west-southwest to east-northeast. Several mountains border the plateau: the Cantabrian Mountains (Cordillera Cantábrica) to the north, the Iberian Cordillera (Sistema Ibérico) to the northeast and east, the Sierra Morena to the south, and the lower mountains of the Portuguese frontier and Spanish Galicia to the northwest. The Pyrenees run across the neck of the peninsula and form Spain’s border with France. There are two major depressions, that of the Ebro River in the northeast and that of the Guadalquivir River in the southwest.

Spain has some of the oldest as well as some of the youngest rocks of Europe. The entire western half of Iberia, with the exception of the extreme south, is composed of ancient (Hercynian) rocks; geologists refer to this Hercynian block as the Meseta Central. It constitutes a relatively stable platform around which younger sediments accumulated, especially on the Mediterranean side. In due course these sediments were pushed by major earth movements into mountain ranges.

Part of Alpine Europe, the Pyrenees form a massive mountain range that stretches from the Mediterranean Sea to the Bay of Biscay, a distance of some 270 miles (430 km). The range comprises a series of parallel zones: the central axis, a line of intermediate depressions, and the pre-Pyrenees. The highest peaks, formed from a core of ancient crystalline rocks, are found in the central Pyrenees—notably Aneto Peak at 11,168 feet (3,404 metres)—but those of the west, including Anie Peak at 8,213 feet (2,503 metres), are not much lower.

A series of sierras trending northwest-southeast forms the Iberian Cordillera, which separates the Ebro depression from the Meseta and reaches its highest elevation with Moncayo Peak at 7,588 feet (2,313 metres). In the southeast the Iberian Cordillera links with the Baetic Cordillera, also a result of Alpine earth movements. Although more extensive—more than 500 miles (800 km) long and up to 150 miles (240 km) wide—and with peninsular Spain’s highest summit, Mulhacén Peak, at 11,421 feet (3,481 metres), the Baetic ranges are more fragmented and less of a barrier than the Pyrenees. On their northern and northwestern sides they flank the low-lying and fairly flat Guadalquivir basin, the average elevation of which is only 426 feet (130 metres) on mainly clay strata.

Drainage

Although some maintain that “aridity rivals civil war as the chief curse of [historic] Spain,” the Iberian Peninsula has a dense network of streams, three of which rank among Europe’s longest: the Tagus at 626 miles (1,007 km), the Ebro at 565 miles (909 km), and the Douro at 556 miles (895 km). The Guadiana and the Guadalquivir are 508 miles (818 km) and 408 miles (657 km) long, respectively. The Tagus, like the Douro and the Guadiana, reaches the Atlantic Ocean in Portugal. In fact, all the major rivers of Spain except the Ebro drain into the Atlantic Ocean. The hydrographic network on the Mediterranean side of the watershed is poorly developed in comparison with the Atlantic systems, partly because it falls into the climatically driest parts of Spain. However, nearly all Iberian rivers have low annual volume, irregular regimes, and deep valleys and even canyons.

Soils

There are five major soil types in Spain. Two are widely distributed but of limited extent: alluvial soils, found in the major valleys and coastal plains, and poorly developed, or truncated, mountain soils. Brown forest soils are restricted to humid Galicia and Cantabria. Acidic southern brown earths (leading to restricted crop choice) are prevalent on the crystalline rocks of the western Meseta, and gray, brown, or chestnut soils have developed on the calcareous and alkaline strata of the eastern Meseta and of eastern Spain in general. Saline soils are found in the Ebro basin and coastal lowlands. Calcretes (subsoil zonal crusts [toscas], usually of hardened calcium carbonate) are particularly well-developed in the arid regions of the east: La Mancha, Almería, Murcia, Alicante (Alacant), and Valencia, as well as the Ebro and Lleida (Lérida) basins.

Soil erosion resulting from the vegetation degradation suffered by Spain for at least the past 3,000 years has created extensive badlands, reduced soil cover, downstream alluviation, and, more recently, silting of dams and irrigation works.

About Spain. History of Spain.

- Home

- >

- About Spain

A short history of Spain in the 20th century.

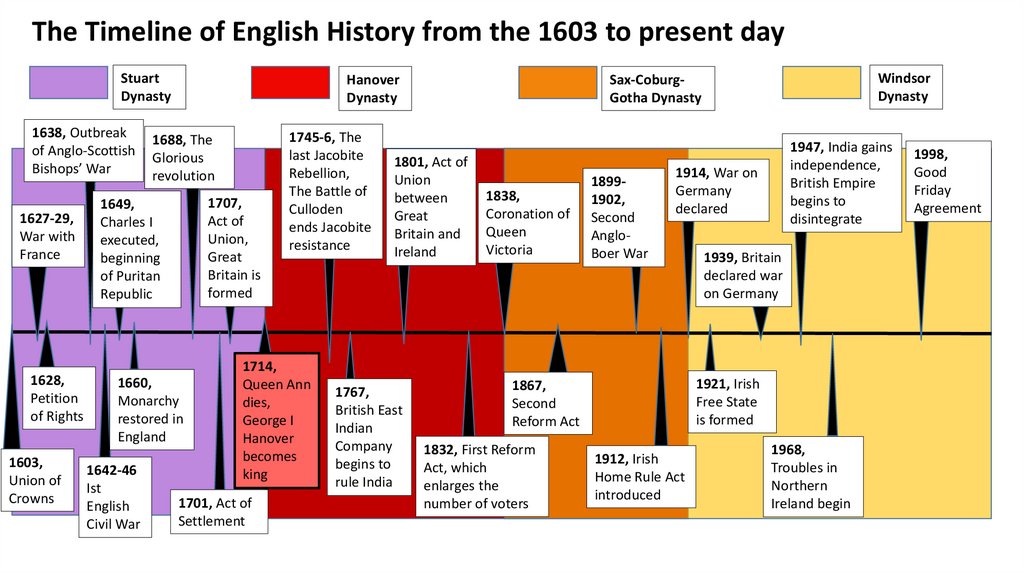

The history of Spain in the 20th century began with the symbolic and tragic year 1898.

The beginning of the 20th century was characterized by a political crisis in Spain. Nationalist movements developed in the regions of Spain: Catalan and Basque nationalists demanded self-government. Spain at the beginning of the twentieth century was mothballed at the level of the constitutional monarchy of 1876, while the new political realities required state reforms in the system of government. In 1909, the syndicalist movement was born in Spain, which later became the basis for the regime of General Franco. From 1912, it becomes clear that the political system of Spain is not able to cope with the challenges of the time.

In 1912, in parallel with the existing political system of Spain, a constitutional monarchy and the ruling parties of liberals and conservatives, a kind of “anti-system” was formed from a multitude of Spanish parties and movements that by that time were in opposition to the existing government. The opposition system included republican parties, socialists, labor movements, as well as regional nationalist parties in Spain.

With regard to Spanish foreign policy, on March 30, 1912, the Treaty of Fez was signed, which turned Morocco into a protectorate of France. According to the Fez Treaty, from November 27, 1912, the territories of northern Morocco around the cities of Ceuta and Melilla, as well as the territory of southern Morocco, on the border with the Sahara, came under the protectorate of Spain in Morocco. In the zone of their protectorates, France and Spain controlled the land policy, the army and the foreign policy of Morocco.

The split in Spanish society became more acute during the First World War in 1914-1918. Despite the fact that the Kingdom of Spain remained neutral in the war, Spanish society was divided into Germanophiles and supporters of the Entente. In addition, the Spanish economy was seriously affected by the war. The revolution in Russia in October 1917 caused a strong resonance in Spanish society. This time Andalusia and Catalonia became the arena of the conflict, they were very sympathetic to the Bolsheviks and the labor movement.

The general strike in Spain in 1917 became a kind of rehearsal for the events of 1931. In addition, in foreign policy, Spain waged a humiliating and unpopular war in Morocco.

History of Spain in the 1930s

In the 1930s the period of political instability did not stop. In 1931, the left-wing parties won the elections in Spain. The king in Spain, seeing public sentiment as a threat to his family, was forced to abdicate. This year was declared the Second Republic in Spain. The regimes of Nazi Germany fought for influence in Spain, and the Soviet Comintern also conducted active propaganda in Spain. February 1936 in the elections in Spain won the People’s Fornt, Frente Popular.

On July 13, Calvo Sotelo, head of the national bloc that united monarchists and conservatives, was assassinated. On July 17, 1936, the Spanish garrisons in Africa revolted.

Spanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War began after an attempted coup in Spain. July 17 1936th Spanish army revolted against the government of the Second Republic in Spain. During the Spanish Civil War, two antagonistic forces clashed: the republican camp of the Popular Front and the National Camp, which was formed primarily by the military from the National Defense Junta, as well as the fascist Falange Spaniards, the Catholic Church, and right-wing conservatives.

October 1, 1936, General Francisco declared himself head of state in Spain and supreme commander. The new head of state of Spain was immediately recognized by Germany and Italy, who sought to persuade Spain to join the Italo-German bloc.

During the Spanish Civil War in Spain, the interests of Germany and Italy, supporting the Francoists, and the interests of the USSR, which provided military and financial assistance to the Spanish Republicans, clashed. However, military support and financial injections from Germany turned out to be stronger than Soviet support for the republican movement in Spain. The Spanish Civil War ended on April 1, 1939, when the last troops of the Red Republican Army were defeated.

During the Second World War, General Francisco Franco tried to keep Spain neutral in the war and non-participation in military blocs. After the end of the Second World War, however, Spain continued to be in political and economic isolation. In 1956, on the wave of developing world independence movements, the former colony of Spain and France, Morocco, gained independence. In 1969, seven years before the centenary of Spain’s constitutional monarchy, General Franco named Juan Cralos de Borbón as successor to the Spanish throne.

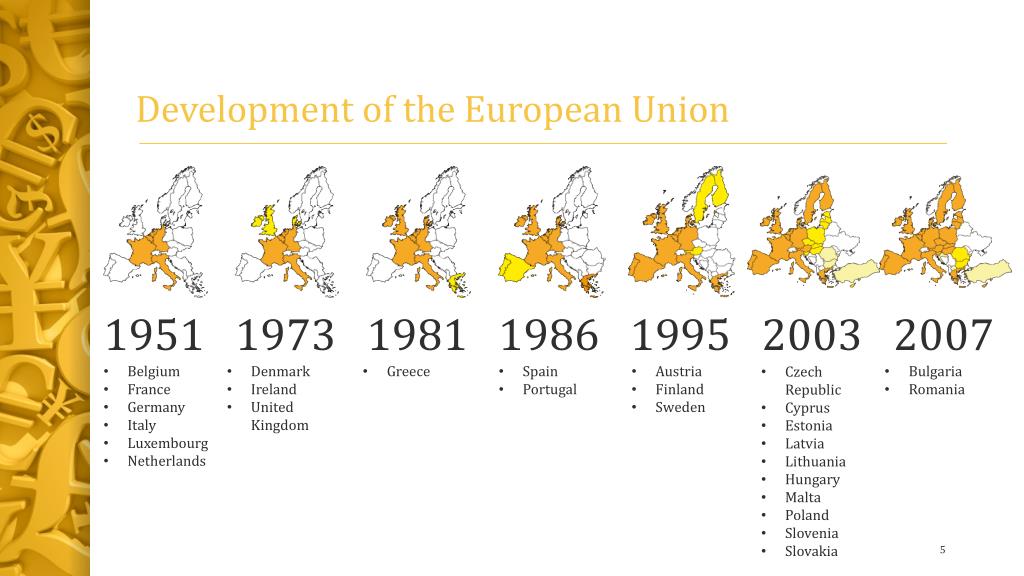

Constitutional Monarchy in Spain

After the death of General Franco in Spain in 1975, a Constitutional Monarchy was again established in Spain, as it had been a hundred years earlier. In 1978, the Spanish constitution was adopted, according to which the official head of state in Spain is the king. The first democratic elections in Spain were won by the Democratic Center party. Adolfo Suarez became the head of the government, or, as they say in Spain, the president of the government. The Suárez government took important steps in the history of Spain: the necessary conditions for the forthcoming accession of Spain to the European Communities were fulfilled.

In the history of Spain, there was another attempted coup d’etat, which occurred after the resignation of Adolfo Suarez at the inauguration ceremony of the new president of the government, Calvo Sotelo. This time, the attempted coup d’état in Spain failed.

Elections in Spain in 1982 led to the victory of the Socialist Workers’ Party of Spain, PSOE.

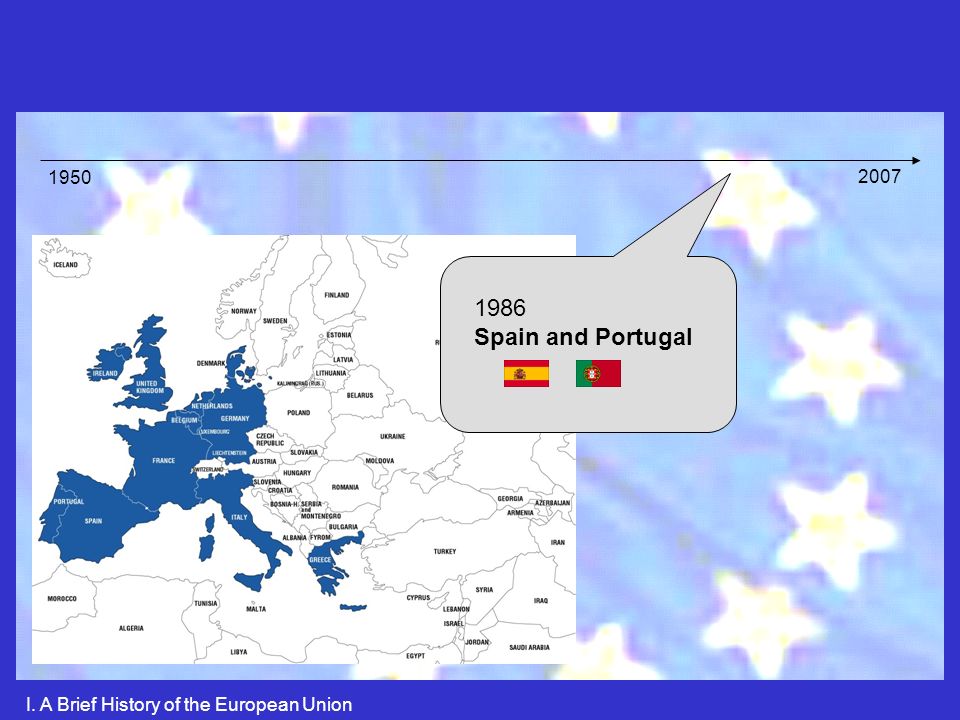

In 1985 Spain became a member of NATO and in 1986 Spain joined the European Community.

Already in the 1990s. Spain begins to strengthen itself as a world cultural and tourist center. A landmark event in the history of Spain is the holding of the Olympic Games in Barcelona, as well as the holding of the world exhibition EXPO 1992 in Seville. José Maria Aznar became the Prime Minister of Spain, who served two presidential terms. Under Aznar, the Spanish economy began to gain momentum and become the ninth most powerful economy in the world.

Spain in the 21st century

In 2002, the euro was introduced in Spain instead of the national currency, the peseta. The city of Salamanca in Spain has been declared the European Capital of Culture. On March 11, 2004, a terrorist attack took place in Spain, the most serious in the history of Spain.

Elections in Spain on March 14, 2004, like almost twenty years ago, brought victory to the PSOE, the Socialist Workers’ Party of Spain. José Luis Rodriguez Zapatero became Prime Minister of Spain. In addition, for the first time in the history of Spain, a woman, Maria Teresa Fernandez de la Vega, took the post of First Vice-President of the Government of Spain.

During their term, Zapatero and Maria Teresa Fernández de La Vega carried out radical political and social reforms, major changes were made to Spanish legislation, such as allowing same-sex marriage or a law on effective equality between women and men.

2008. March 9, the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party again won the national elections in Spain, winning 169 parliamentary seats (5 more than in the 2004 elections).

The 2008 elections strengthened the two-party system in Spain. In the first half of 2010, Spain held the presidency of the European Union, which led to promising prospects for Russia, aimed at increasing the flow of tourists and investments to Spain from Russia. These prospects have been repeatedly stated and continue to be stated by the Embassy of Spain in the Russian Federation.

About Spain

Visa to Spain

Study in Spain

Work in Spain

Banks in Spain

Taxes in Spain

Residence permit in Spain

Business in Spain

Property in Spain

Lawyer in Spain

Nota Simple

Spain at a glance – BBC News

Spain is located at the crossroads of Europe and Africa between the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea, a country whose history and culture is striking in its diversity.

Centuries of expeditions and conquests greatly strengthened the country’s military power, and in the 16th century Spain became a world power.

One of the most important events in the new history of Spain was the bloody civil war 1936- 1939 and the subsequent right-wing dictatorship of Francisco Franco, which lasted 36 years.

SUMMARY

Photo Caption,

Flag of Spain

After the death of General Franco in 1975, already under the rule of King Juan Carlos, Spain emerged from an endless cycle of coups, uprisings and civil wars and moved towards democracy.

The 1978 constitution, which is still in force today, enshrined not only the idea of the inviolable unity of the Spanish nation, but also a respectful attitude towards the diversity of cultures and languages represented on the territory of the state. The constitution also defines the rights of each of the 17 autonomous regions within the country.

Each region has its own degree of autonomy.

Andalusia, Valencia and the Canary Islands, in turn, also have special powers. While Asturias and Aragon are making attempts to consolidate the rights to use the local language.

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it’s important and what’s next.

episodes

The End of History Podcast

In 2006, the people of Catalonia, where a referendum was held on the question of expanding autonomy, voted for greater independence from Madrid.

As a result of the referendum, the Catalans received the status of an independent nation within Spain.

In addition to resolving the issue of autonomy of the regions, one of the most serious internal political tasks of Spain is to resolve the situation in the Basque region.

ETA separatists reportedly killed more than 800 people during the group’s forty-year struggle to create an independent Basque state.

In March 2006, ETA declared a ceasefire in an attempt to promote the democratic process in the region. This move led to a split in public opinion.

Hopes for a peaceful resolution of the conflict were dashed when, on the eve of 2007, ETA broke the March truce and claimed responsibility for bombings at Madrid’s Barajas International Airport. In June 2007, the ceasefire was finally terminated.

Until 2008, the Spanish economy was considered one of the most prosperous in the EU. The country’s main source of government revenue was the booming housing market and tourism, which in 2008-09years were hit by the global crisis, thereby significantly slowing down the pace of the country’s economic development.